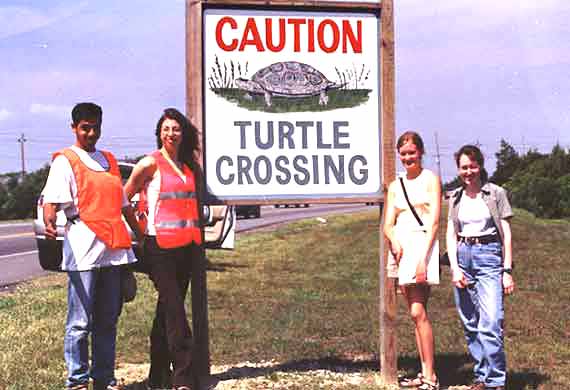

Firoz Ahmed and Kristen Boccumini, left, and Stephanie Hurder and Suzette

Girouard, right, with prominent turtle crossing sign near the Wetlands Institute.

|

The following articles have been written by the NYTTS Scholarship students:

Sovannara Heng (Cambodia), Jichao Wang (China), and Firoz Ahmed (India).

Constructing a predator exclosure for a terrapin nest

on the Nature Trail at the Wetlands Institute

|

|

Protecting Nest Sites

Protecting Nest Sites

by Sovannara Heng

Today I helped with another predator exclosure for a diamondback terrapin nest along the nature trail at the Wetlands Institute. We build the exclosures to protect the eggs from predators and also so that we can get the baby terrapins when the eggs hatch.

To make the exclosure, we dig a shallow trench around the nest about 4 to 6 inches deep. Then a circle of stiff plastic mesh is set down along the trench, extending about 4 to 6 inches above ground level, and ties are used to close one end to the other. Then we lay a length of 1 x 2 board across the top edge of the circle of the mesh to stabilize it. On top of the board and the top edge of the mesh we will lay flat circular piece of the plastic mesh and secure it with more ties.

A completed exclosure protects nest and hatchlings

|

Once the exclosure is completed, we number it for our records. If we can capture the female terrapin before she leaves her nest, we will check to see if she has a PIT tag (a “Passive Integrated Transponder”) — a microchip that may have been injected into the terrapin from an earlier capture (also see photo below). Otherwise, we will give her a PIT tag for later identification. We will measure her and take a photo for our records as well.

So far this season we have built 20 exclosures. I look forward to seeing hatchlings from some of the first exclosures of the season in about six to eight weeks.

The Diamondback Terrapin Incubation Project

by Jicaho Wang

During this month, I am participating in the diamondback terrapin road patrol and incubation project, which is being undertaken by the Wetlands Institute and Richard Stockton College of New Jersey.

It is now the diamondback terrapin's reproductive time. Many female terrapins cross the local roads to look for nest sites. When the turtles are struck by motor vehicles, we take the injured and dead turtles to the lab. The dead turtles' eggs are removed from the carcass, cleaned, and measured, then placed into the incubator.

Road patrol records data from a road-killed terrapin.

|

Every day we patrol for turtles killed on the road every three hours. Each time we find a turtle killed on the road, we record the turtles' locality, time, etc., data which are very useful to analyze the turtle's activity and population status.

The eggs will hatch in seven to twelve weeks. Higher incubation temperatures are used to produce females, which will help replace those that have been killed on the roads. The little hatchlings are fed for about one year. When the hatchlings are big enough to better survive in the wild, we will release them, usually with the assistance of the public (often school children), which also helps to educate the children and the general public to protect the animals and our environment.

Turtle Patrols on the Roads in Southern New Jersey

by Firoz Ahmed

I have been going out on road patrol since the 26th of May, a couple of days after I landed in U.S. from India to join the Wetlands Institute internship program. For more than ten years during the nesting season, the Wetlands Institute has run round-the-clock road patrols to retrieve dead terrapins from the local roads (to save the viable eggs for incubation) and, of course, to also save terrapins crossing the roads. Road patrols are usually carried out by the summer interns and volunteers five times a day (midnight, 5, 8, 11 a.m., and 2 p.m.). Interestingly, the terrapins are nesting earlier this summer (before the 25th of May). Nesting usually starts during first week of June.

Using a portable reader, terrapin remains are checked

for the presence of an identifying PIT tag,

|

Two to three people, and sometimes more, may join a patrol, which is roughly a 20 mile transect in the southern New Jersey in the vicinity of the Wetlands Institute. Starting and ending at the Wetlands Institute, the transect covers Stone Harbor Boulevard, Third Avenue, Avalon Boulevard, Sea Isle City, Central Avenue, Landis Avenue, and JFK Boulevard.

During breeding season (June–July) the terrapins come out of salt marshes to find a suitable place above the high-tide level to lay eggs. However, the marshes, highlands, and sand dunes are criss-crossed by a number of roads, which the turtles attempt to cross. All are not lucky to successfully cross the road and return safely to the marsh; many are run over by vehicles. During weekends the traffic is very high here, and the number of dead turtles increases. According to Dr. Roger Wood, on our transect alone, more than 500 terrapins die every year.

Brightly colored safety vests help protect

patrol members from speeding traffic.

|

The main purpose of the road patrol is to record the number of dead turtles and collect the ones with viable eggs. We also measure the carapace and plastron length of each dead turtle. On reaching the Institute we remove the potentially viable eggs (a procedure called eggectomy) and save them for incubation at the Richrd Stockton College of New Jersey.

The main purpose of the road patrol is to record the number of dead turtles and collect the ones with viable eggs. We also measure the carapace and plastron length of each dead turtle. On reaching the Institute we remove the potentially viable eggs (a procedure called eggectomy) and save them for incubation at the Richrd Stockton College of New Jersey.

We always wear bright-colored vests with reflective stripes (a vest worn by road workers) to save ourselves from the speeding trucks and cars while collecting dead turtles or saving live ones crossing the roads — a necessary precaution to not become martyrs for the turtles!

It is not fun to collect the dead turtles — never. Sometimes it is heartbreaking.

Yesterday (11 June 2002) my intern colleagues Jichao, Meredith, and Christina had a bitter experience. On the 2 p.m. patrol at Central Avenue they spotted a turtle crossing the road. Immediately they stopped the approaching cars to rescue the turtle, but a truck coming from the other direction did not care to stop and smashed the turtle. They were upset watching the gravid terrapin being run over and not being able to rescue it.

“It is disgusting,” Jichao said. Meredith was about to cry when she was describing what happened. "It was distressing to see the yolks of the eggs of the terrapin spreading over the road," said Christina.

Perhaps it is a scene that will be disturbing them for many many days to come.

|