November 24, 2008

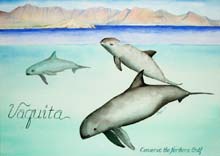

A year ago last July, when marine biologists Robert L. Pitman and Lorenzo Rojas-Bracho wrote in our pages about the vaquita (Phocoena sinus), the tiny, critically endangered porpoise that lives only in the upper Gulf of California,

there were only an estimated 200 individuals of the species left. Now, the official estimate is 150. Every year, forty to eighty vaquitas drown in the entangling gill and drift nets of fishermen and shrimpers from the local communities of San Felipe, Golfo de Santa Clara, and Puerto Peñasco—collateral damage in the villagers’ struggle for a living.

I stayed up most of the night confirming the grim facts in Pitman and Rojas-Bracho’s article and grieving. It was the first I’d ever heard of the vaquita—which wears an enigmatic little black-lipsticked smile, as if the Mona Lisa were a goth—and it was like meeting an enchanting stranger on his or her deathbed. For the world’s smallest cetacean, no more than five feet long, time is fast running out.

But if there are fewer vaquitas than there were a year and a half ago (and, as we’ll see, maybe not!), there may also be more real hope for them. Although they live only in Baja California’s armpit, they’ve now (thanks to tireless advocacy by our authors and others) got the whole North American continent’s attention. They are the focus of a NACAP, or North American Conservation Action Plan, which you can download in three languages here [PDF]. The document attests to the growing collaboration between the U.S., Canada, and Mexico in identifying and protecting the living treasures of our common continent. In a telling detail, to qualify a species must be “charismatic,” presumably to enlist the public sympathy that leads to effective political pressure. Too bad for some endangered warty toad, I guess, but good for the vaquita—and the NACAP rolls out a detailed plan for bringing it back from the brink.

It boils down to two points: the drownings in fishing nets have got to stop, and the fishermen have got to make a living. To a pessimist those might sound irreconcilable—but even my cats now eat dolphin-safe tuna. Back in the late 1970s, when I interviewed University of Santa Cruz professor Kenneth S. Norris, that seemed to some like an impossible dream. Ken, on the other hand—one of two scientists who identified the vaquita [PDF] as a distinct species in 1958, by the way—was absolutely convinced that it could be done, and that the only way to do it was to draw on the knowledge and honor the interests of tuna fishermen. While deep and an ecologist, Ken was no human-hating “deep ecologist”; so far from imagining that the planet would be better off with far fewer people (or none at all), he believed that humans and their industries are an integral and entitled part of nature—and smart enough to figure out how to be a less destructive part. Ken traveled on tuna boats and observed their process, and he helped to design a purse seine with a dropping panel where crew members in wetsuits or rubber rafts could usher trapped dolphins out, one of several lifesaving technological innovations born of science-and-industry collaboration. Meanwhile, consumer boycotts and strict dolphin-safe standards established by nongovernmental organizations, notably Earth Island Institute, steered U.S. tuna canners away from fish caught by netting dolphins at all. The result (from a 2005 subscription-only article, references omitted):

[I]mproved fishing gear and rescue efforts by the fishermen, combined with the effects of national legislation and international agreements, have resulted in a reduction in incidental dolphin mortality from an estimated hundreds of thousands of animals annually in the early 1960s to less than 3,000 animals annually since 1998.

That story isn’t over; despite the dramatic drop in reported mortality, the population of the spotted dolphin, Stenella attenuata, that fishermen used (and Mexican fishermen, among others, still use) to find and catch associated schools of yellowfin tuna still hasn’t recovered as it should. Along with unreported kill of unknown magnitude, the stress of being chased may be interfering with health and reproduction. One lesson learned is that the price of protecting a species is eternal vigilance: in a battle that has lasted six years, environmental activists successfully sued the Bush Administration and blocked its attempt to weaken dolphin-safe standards in Mexico’s favor. Another lesson is that Ken Norris was right: fishermen can and must be a vital part of the solution.

The vaquitas’ plight, so much smaller in scale, is much more acute in urgency: not only intelligent, sociable individuals, but an entire species stands to be wiped out forever. This is an emergency. The NACAP [repeat link, PDF] urges swift and strict enforcement of a total entangling-net ban within the vaquita refuge that the Mexican government established in 2005,

along with educational initiatives to raise local awareness (already well underway) and “two basic socioeconomic strategies” for cushioning the economic impact on fishermen: “technological conversion (use of fishing gear that does not carry the risk of vaquita entanglement)” and “productive conversion (providing fishermen with alternative livelihoods).” Fisher families who agree to change their way of fishing or of living will need temporary subsidies to help them through the transition. Given such incentives, many have expressed a willingness to do so, and some already have. The program continues to be fine-tuned.

To monitor whether these measures are being honored and enforced, and whether they are effective in edging the vaquita back from the brink, data will be needed of a kind that’s very hard to obtain. Vaquita are not only rare but shy and elusive, traveling mostly in twos and threes, spending little and inconspicuous time at the surface. Current methods of acoustic tracking are inadequate to detect them. So the Mexican government asked the international scientific community to come to the Gulf of California and test sensitive new methods for monitoring vaquitas’ numbers and movements. The result has been a unique collaborative expedition that’s wrapping up in the Gulf right now, as this post comes online. While much data analysis lies ahead, the expedition’s two lead scientists, Lorenzo Rojas-Bracho (Mexico), who also coauthored our article, and Barbara L. Taylor, (NOAA Fisheries Service, U.S.A.) have been kind enough to share their preliminary impressions with Natural History’s readers. Between the lines of the following report “fresh off the boat” you may read, amid the urgency and determination, a guarded glimmer of hope. (The filmmakers of Whale Trackers, who accompany and document cetological research expeditions, were on board this one, and they provide a rare close-up encounter with the vaquita to accompany the science.)

* * *

Brief Summary Report of Vaquita Expedition 2008

Vaquitas are a critically endangered porpoise found only in a small part of the upper Gulf of California, Mexico. This porpoise has the smallest distribution of any marine mammal. Recent acoustic data indicating a decline in vaquita numbers taken together with the probable extinction of the Chinese River dolphin prompted the government of Mexico to take unprecedented steps to save their porpoise from the same fate: extinction resulting from accidental deaths when animals drown in fishing nets.

The recently concluded Vaquita Expedition 2008 was a joint US-Mexican effort to provide the best scientific data possible to aid the government of Mexico in conservation decisions for the vaquita. The primary goal was to use passive acoustics to see whether conservation actions to reduce the level and area of gillnetting are allowing vaquita numbers to increase. Three vessels were used: the Koipai Xú-Yá, which has been the primary acoustics research vessel for Mexico and led the work on stationary acoustic research; a 24-foot (9 m), a sailing vessel that towed an acoustic array; and U.S. NOAA research vessel David Starr Jordan, which deployed research buoys for autonomous acoustic recorders, conducted oceanographic work to better understand vaquita habitat, and carried out visual surveys. Scientists came from Mexico, the U.S., Canada, United Kingdom, Japan, Germany, Australia and South Africa.

The inventors of the acoustic equipment used to detect porpoises came to the upper Gulf of California so that they could modify their equipment for this expedition. They discovered that the upper Gulf was very noisy in the high frequencies used by vaquita to echolocate. Despite the challenges, all three types of vaquita detectors successfully detected vaquita. The array towed by the sailboat also detected vaquitas in very shallow water close to one of the main fishing villages. The acoustic detections confirm the good news also seen by the visual team using high powered binoculars: vaquita are not extinct and their distribution is roughly the same as it was ten years ago.

However, data from the research buoys show great differences in vaquita densities within their known range. Some buoys detected no vaquitas in the 2 month research period, while other buoys detected vaquitas almost daily. Scientists will use these data to design an acoustic monitoring program which will determine whether the current conservation actions to reduce gillnet mortality are being successful.

—Barbara L. Taylor and Lorenzo Rojas-Bracho

Lorenzo Rojas-Bracho adds in an e-mail:

I think all of us in the vaquita plight recognize that we are in a far better situation than we have ever been. Just compared to the 1997 vaquita cruise we see very impressive enforcement by PROFEPA

(Mexico’s Attorney General for the Environment). We could say that the vaquita refuge is pretty clean compared to what we saw in previous years. The Government is implementing the vaquita conservation action plan (PACE-vaquita) and has invested so far close to $18 million USD to eliminate a third of the fishing effort. It has been announced by authorities that they will continue in 2009 with the program to have a free-of-gillnets Upper Gulf. We all are optimistic that it will be possible to save the vaquita.

(Annie Gottlieb) |

Comments (add yours!)

Return to November home

|