|

February 5, 2008

YOU’VE HEARD the cliché, meant to reflect a larger truth about how a language reflects its speakers’ experience, environment, expertise, and cultural preoccupations: “Eskimos have dozens of words for snow.” (And “Germans have as many for bureaucracy.”) Or twenty-eight. Or fifty. Or over 100. (Nope, that was a hoax—a funny one, too.)

Well, no, they don’t.

First of all (as I vaguely knew before my crash course in all things Arctic, fact checking Shari Gearheard’s “A Change in the Weather”), there aren’t really any “Eskimos.” Like so many European-settler names for indigenous peoples, the word was borrowed from unrelated (and sometimes inimical) neighbors— outsiders looking in. “Eskimo” was once believed to be an Abenaki put-down, “eater of raw meat” (why are so many insults based on what people eat?) but is now thought to derive more politely from Ojibwa for “to net snowshoes.” The related Arctic peoples the word once embraced, in Canada, Greenland, Alaska, and Siberia, now tend to get lumped together under “Inuit” instead—but rather than be misnamed for their eastern cousins, Alaska’s Yuit and Inupiat would prefer to be called Eskimos, thank you very much, to the delight of the anti-political-correctness crowd.

Second of all, look at any purported list of “Eskimo words for snow,” and you’ll see that a lot of them are actually words for ice—specifically the sea ice on which these Arctic dwellers hunt and travel, and that Gearheard, her hosts, and their dogsleds nearly fell through because it has so shrunk and thinned under the onslaught of rising temperatures. In an unsourced but plausible quote, one Nukapinguaq said, "White men think of ice as frozen water, but Inuit think of water as melted ice. To us, ice is the natural state." Not anymore! It’s their intimate knowledge of ice—its topography, its timing, even its texture and taste—as well as snow, wind, and wildlife that’s making Arctic elders such crucial collaborators for scientists studying climate change.

Third, and best of all—well, let this one speak for itself:

[T]he Eskimoan language group uses an extraordinary system of multiple, recursively addable derivational suffixes for word formation called postbases. The list of snow-referring roots to stick them on isn’t that long: qani- for a snowflake, api- for snow considered as stuff lying on the ground and covering things up, a root meaning “slush,” a root meaning "blizzard", a root meaning "drift", and a few others—very roughly the same number of roots as in English. Nonetheless, the number of distinct words you can derive from them is not 50, or 150, or 1500, or a million, but simply unbounded. Only stamina sets a limit.

That does not mean there are huge numbers of unrelated basic terms for huge numbers of finely differentiated snow types. It means that the notion of fixing a number of snow words, or even a definition of what a word for snow would be, is meaningless for these languages. You could write down not just thousands but millions of words built from roots that refer to snow if you had the time. But they would all be derivatives of a fairly small number of roots. And you could write down just as many derivatives of any other root: fish, or coffee, or excrement.

And the derivatives wouldn’t all be nouns. If you wanted to say, "They were wandering around gathering up lots of stuff that looked like snowflakes" (or fish, or coffee), you could do that with one word . . . .

There’s more. If, like me, you’re a word freak as well as a science geek, you may want to bookmark Language Log. Here and here are other posts on the “Eskimo words for snow” meme as it collides with global warming.

The insight that the death of any language is the loss of an irreplaceable understanding of the world, as

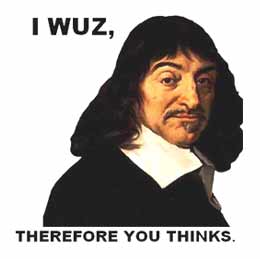

Sarah Gray Thomason warned last month about Salish-Pend D’Oreille (“At A Loss for Words”), stems from the work of the early 20th-century linguist Benjamin Lee Whorf. Reading the real story about “Eskimoan” languages, ice, and snow makes you realize that the real genius of a language resides not in its vocabulary, but in its grammar. What’s most different about those languages isn’t their take on H20, but the embeddedness of the speaker in relationship, action, and landscape. By comparison, our surgical separation of subject, verb, and object is so... what? Help me out here… so Cartesian.

Sarah Gray Thomason warned last month about Salish-Pend D’Oreille (“At A Loss for Words”), stems from the work of the early 20th-century linguist Benjamin Lee Whorf. Reading the real story about “Eskimoan” languages, ice, and snow makes you realize that the real genius of a language resides not in its vocabulary, but in its grammar. What’s most different about those languages isn’t their take on H20, but the embeddedness of the speaker in relationship, action, and landscape. By comparison, our surgical separation of subject, verb, and object is so... what? Help me out here… so Cartesian.

(Annie Gottlieb) |

Comments (add yours!)

Return to February home

|