Click photos for details.

|

Chelonian Research Institute 402 South Central Avenue Oviedo, Florida 32765 Chelonian Research Institute |

Peter Pritchard Named

Floridian of the Year

Photos by Julie Larsen Maher / Wildlife Conservation Society.

Click photos for details. |

Peter Pritchard Named Floridian of the Year Photos by Julie Larsen Maher / Wildlife Conservation Society. |

|

A Natural Champion by Ludmilla Lelis, Sentinel Staff, January 7, 2001 Copyright © 2001, Orlando Sentinel, reprinted with permission. Twenty years ago, Peter C. H. Pritchard met the man who should have been his sworn enemy. Pritchard arrived in Mexico as an ambassador for the Florida Audubon Society, armed with weighty science degrees and a passion to protect turtles. He came face to face with the owner of a turtle slaughterhouse, who had become rich harvesting and then selling the reptiles’ meat and shells.

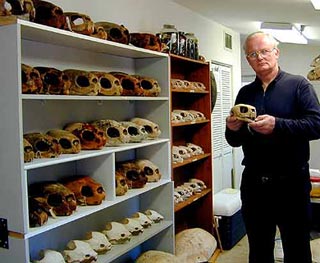

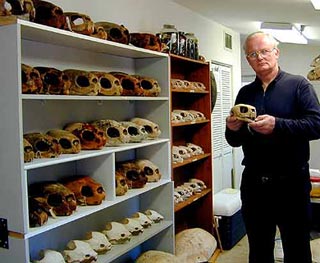

The strategy worked, just as it has for other ecological causes pioneered by other environmentalists, from saving the Everglades to cleaning up the nation’s water and air. As a symbol, and a leader, of that movement, as well as a dedicated scientist and a diplomat among conservationists, Peter Pritchard, 57, has been chosen by the Orlando Sentinel as its 2000 Floridian of the Year. Pritchard is one of the world’s foremost experts on turtles and tortoises. He has traveled to more than 90 different countries, including Guyana and Costa Rica, where he made environmental protection of turtles his goal in meeting with people who once depended on the animals for food. Fellow conservationists hail his ability to reach out to others — from royalty to remote tribes, from financial mavens to suburban pet-turtle owners — and bring them into his cause. In his honor, three turtle species are named after him. This past year, Time Magazine declared him a “Hero of the Planet.” [See “Peter Pritchard: Tickled About Turtles.”] Throughout it all, he has continued a rigorous scientific quest, systematically collecting turtle and tortoise specimens. He has brought his knowledge to Oviedo, where he founded the Chelonian Research Institute, named after the scientific category for turtles and tortoises. Inside an Old Florida homestead under a canopy of live oaks and sabal palms, the Institute holds the world’s most complete collection of turtle skeletons, fossils, and preserved specimens. He has made the sprawling Seminole County town an unlikely capital of turtle knowledge, attracting scholars from around the world.

The following year, he moved to Gainesville, where Carr was a University of Florida professor, and earned his Ph.D. in zoology. The switch suited him, allowing him to become a modern-day English explorer, trudging through the Okeefenokee swamp to film alligator snapping turtles, or sailing to beaches in the Galapagos with his wife, Sibille, and his young sons, all in the name of science. Florida was an ideal home for someone who wanted to study chelonians, the biological classification for turtles and tortoises. Loggerheads, leatherbacks, and green sea turtles nested along the beaches, while box turtles and gopher tortoises burrowed below ground level. Under Carr’s tutelage, Pritchard learned about both the biology and the environmental stewardship of turtles. In his twenty-three-year career with the Florida Audubon Society, Pritchard led many conservation causes and helped to stem one major cause of turtle deaths. Marine turtles regularly were trapped in the huge fishing nets that trawled the Gulf of Mexico. They drowned by the thousands, unable to swim up for oxygen. But a new device offered an escape hatch for turtles. Shrimpers balked at proposals to require Turtle Excluder Devices (TEDs), and Pritchard tried to depend on cooperation with the industry. Though the Gulf fishermen despised TEDs, some Atlantic Coast shrimpers were using them successfully. His patient lobbying paid off when the National Marine Fisheries Services made TEDs mandatory. He has championed other Florida causes, including working on protection of the manatee and editing the first edition of a six-volume series of biology texts titled Rare and Endangered Biota of Florida. He also co-authored Saving What’s Left, a manual on conserving Florida’s pristine lands. Written after the state started its first ambitious land-buying program, the book aims to explain why land conservation is needed and how the programs work. Besides land conservation, Pritchard worked on another study about attempts to restore wildlife habitat to an abandoned land mine. Though mining is destructive, it isn’t permanent and a closed mine can be restored to become wetlands or scrub. Another option is to build homes, taking development away from more pristine areas. During a Polk County study, he found that turtles at an abandoned phosphate mine had a high amount of radioactive minerals in their bones, the result of eating plants among the radioactive debris. He even helped to jumpstart efforts to save the Florida panther, by calling the first informal meeting of panther experts to discuss whether the animals could be saved. From that first conference developed a team that put together a strategy to help the species recover from the brink of extinction. However, turtles remain the centerpiece of his conservation work. Through his writing, film, and television work, he has made turtles popular, building support for their conservation. Such single-minded devotion to an animal has an important underlying goal — environmental protection of all living creatures. “Turtles don’t exist in a vacuum,” said turtle expert Dr. Anders Rhodin. “Saving turtles means preserving the beaches where they nest. It means keeping the oceans clean of the garbage and toxins that can also poison the fish people eat. It means reducing pollution on the land where tortoises are burrowing and where people make their homes.” If turtles, as an integral part of the cycle of life, can’t survive, and if turtles don’t have an environment where they can live, humans may not eventually survive. “If other species lose out, we lose our life support,” Pritchard said. “Clean air and clean water are things you can take for granted until they’re gone.” As the son of an Australian anatomy professor and the husband of a Guyanese journalist, Pritchard stretched his work around the world. Former Florida Audubon President Clay Henderson says jokingly that he kept a globe on his desk to “help me know where Peter was that day.” Pritchard’s international fieldwork is probably his greatest legacy. His research, conservation work, and consulting jobs have taken him throughout the Caribbean, South America, Africa, Southeast Asia, and the South Pacific. In particular, Pritchard’s work in Guyana, with the native Arawaks, helped to shape and confirm his art of conservation through consensus and mutual respect. Guyana’s Caribbean coastline harbors one of the largest pockets of people who are kin to the tribes that first encountered Christopher Columbus. European colonization of the Americas, with its cycle of war, disease, and slavery, decimated the indigenous peoples, but these remote groups in Guyana survived. Turtle meat has traditionally been part of the Arawak diet. Green sea turtles and leatherbacks can grow to enormous sizes — weighing half a ton or more — and the females lay dozens of eggs in beach dunes. Over time, the marine sea turtles, including olive ridleys and hawksbills, couldn’t rebound from the demands of hunting, becoming more and more rare each year. The Guyana tribes posed a huge dilemma for Pritchard. Marine turtles were nearing extinction, but the Arawak culture and way of life is arguably just as endangered. He began befriending the people and talking with them about why their turtle catch grew smaller and smaller each year. He found grants to start chicken farms as an alternative source of protein. He hired tribesmen to tag the turtles for research and police the nests to protect them from poachers. And he reached out to the youngest generations, teaching them about environmental protection. Threats to the turtles of Guyana still exist, but years later the slaughter has subsided and the number of turtle nests is increasing. Pritchard said the strategy worked because he has included Arawaks in the wildlife effort, rather than having turtle protection imposed by a foreigner and enforced by the government. Between tribal talks and government meetings, Pritchard remains a scientist at heart. Throughout his journeys, he has collected information and actual turtle specimens, helping to fill a scientific void. He has helped to build much of the core of turtle knowledge: Where do the 290 different species live? How do they differ? What do they eat? Where do they nest? And he has produced from this information six major turtle books, countless scholarly articles, films and documentaries. His life’s work — amassed in 6,500 turtle and tortoise specimens — is on display in Oviedo. Pritchard founded the Chelonian Research Institute in 1998, where he displays the world’s most complete turtle collection, offering examples from every genera of turtle and 90 percent of the different species. With the specimens hung next to paintings and indigenous carvings, the Institute doesn’t seem institutional, but rather a home for turtle science. An impressive 6-foot-long green turtle shell hangs next to a fireplace in the living room, furnished with carved tables, upholstered seating and prints from the Czech Republic and Madagascar. A valued fossil of an extinct French turtle sits on a bookshelf, making it easy to pick up and view closely. Young hatchlings swim circles in the den’s aquariums, and hundreds of jars of preserved turtles are tucked away in an attic closet. His actual home across the street houses Galapagos tortoises and a herd of alligator snapping turtles. And Pritchard prides himself on the fact that turtles weren’t killed to become part of the collection, but were salvaged from rubble piles or discarded nests. The Institute represents a dream come true for Pritchard — offering a sanctuary for knowledge and learning, open to Florida schoolchildren and international scholars alike. But even the Institute isn’t safe from the increasing demands of growth, with city plans to widen State Road 434, just outside its doors. Pritchard has both optimism and pessimism about the future of conservation. “People are the problem and people are the solution” is his primary adage. There are few people who are truly villains of the environment. People need to have food, to have homes, and to earn a living. He stresses that he’s not an enemy of capitalism, but that the economic engines of the world need to be compatible with the environment. And he’s optimistic that it can be done. Finding a delicate balance between humanity and the rest of the world will be a great challenge. The environment supports turtles, pandas and birds, but it’s supporting more humans every year. That’s six billion people and still counting. “If one is alive at all, one has an impact on the environment, and the curve of human expansion is pretty dizzying,” he said. “That is a tremendous consumptive impact upon an environment that is crying for mercy.” | |||||